Let’s go back to Rotterdam, shall we? Previously this summer, I wrote about interpreting damaged churches in the city and the Erasmus Experience exhibit in the Rotterdam Public Library. Now, I want to talk about the Maritime Museum of Rotterdam, a museum visit that I crammed into a late afternoon after returning from Kinderdijk. (There will be no post about Kinderdijk because it would just be pictures and fawning, but the further and further away I get from it, the more thoughts I have about how the site was interpreted.) The Maritime Museum gets rave reviews on travel guides, which is why I chose it over the city museum or other historic sites. I’d already taken a boat tour of the industrial harbor and ridden a water taxi to Kinderdijk, but I wanted to learn more about how the shipping industry had evolved from what I knew about the Dutch Golden Age into the massive industrial power that the Rotterdam port is today.

So I raced to the Maritime Museum, with only about two and a half hours to go through it. I say only because I found, upon my arrival, that the museum had a little mini-harbor behind it, an outdoor museum of boats in the actual water, that closed earlier than the rest of the museum. Some of the small boats could be boarded, while some primarily demonstrated types of exteriors or the industrial machinery visible on them. All around me, kids skipped on and off of boats, and the signage reminded me more of an American science museum than a history museum. When I went inside, that perception continued to grow—they had whole exhibits geared specifically toward children and families with hands-on activities that seemed state-of-the-art in their execution.

Exterior of the Maritime Museum with part of the mini-harbor of boats and cranes. (My photo, 2018)

Once inside, I hurried past the rest of the children’s exhibits and upstairs to the main exhibit, having no idea what would come next and only knowing its name: the Offshore Experience. When I reached the top of the entry ramp, the museum employees told me that I needed to hurry because the “training” had already started. They ushered me into another room, past countdown clocks and increasingly industrial-looking décor. In the next room, I found a video screen and seating that reminded me of the Star Wars ride at Disney World—the one where you watch a video and the seats shake and sound effects come from all sides, but you never actually leave that one room until you exit on the other side. In this case, the video explained that we were all training for work in the offshore energy industry and that, while the work may be hard and dangerous, it’s an increasingly important part of the worldwide shipping industry. After the video ended, we stepped into the next room, where we found hard hats and fluorescent vests that we should wear throughout the rest of the exhibit. It was truly wild - you can see some of that in the video below.

The hard hats and vests turned out to be far more than just costumes—the rest of the exhibit was HIGHLY interactive. Visitors moved from station to station trying out video game-style and augmented reality tasks that gave explanations of actual jobs on offshore rigs and tested the ability of the “trainee” to complete them. Signs and the initial training video told us that we would need to complete three of these tasks to successfully complete our training, so I tried a few. And they. were. HARD. I flat-out failed one that involved waving a large shipping container dangling from a crane into place on the dock. (This will likely come as no surprise to anyone who’s ever seen me play Mario Kart.)

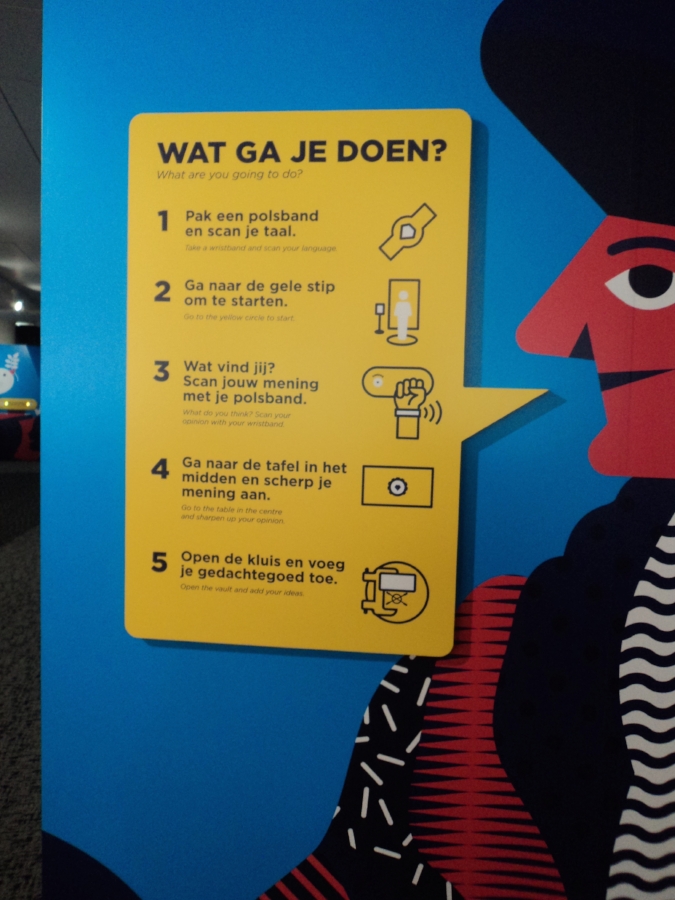

When I finished with these interactive activities, I was directed to an elevator, which took me down to another floor. Training was over, but it was now time to learn a little more about the business side of offshore activities and renewable energy. They had video screens with real (real?) entrepreneurs and scientists who proposed plans for finding, developing, and using energy across the planet—each video was in its own little booth, which made it feel as if these experts were pitching to me directly. Before heading out of the exhibit and back into the museum, they asked you to vote for the one that seemed best. The rest of the museum was split between kid-friendly, immersive experiences and more traditional museum displays of exceptionally beautiful and unique artifacts from the shipping industry.

I’ve been wracking my brain since I returned from my trip to think of any exhibition or other experience that mimicked the Offshore Experience in its total synthesis of experiential learning principles. Still, there are few comparisons I’ve remembered. There’s the Titanic Exhibition that has been touring for years and years, where you receive a boarding pass upon entering, walk through meticulous recreations of the rooms on board to learn about the history of the voyage, and then check the lists at the end to see if “you,” the name on your boarding pass, numbered among the dead. It productively asked you to get inside the mind of someone on the Titanic, including that person’s particular gender, ethnicity, and social class. Besides that, however, I can think of little else. It’s a salient difference that the Titanic exhibit does most of their immersion without the aid of technology, but few historical events hold so much sway on the American imagination.

With the Maritime Museum, I continue to feel enthusiastic about the Dutch museum world and the lessons that their efforts to interpret their art and history can teach us. Choosing a topic like offshore energy development for a permanent exhibition speaks volumes about how they view the capacity of museums to affect earth’s future. Asking people to engage with contemporary debates at the end of the exhibition applies and tests the material that visitors have just learned, and I suspect that that increases the likelihood they might still be thinking about it weeks later. Much like the Erasmus Experience, which used its technology to thoroughly engage visitors rather than supplement a primary analog experience, the Offshore Experience provides a model for high-tech exhibitions that do not sacrifice content to draw and educate audiences.