My dad (lower right), my uncle, my grandmother, my grandpa.

I’ve been thinking about family history a lot lately—both mine and other people’s, as well as how we practice family history in historical societies and as amateur genealogists. If the stories I’ve heard over the years are true, on my dad’s side alone, my ancestors include:

A Belgian anarchist descended from French Huguenots who fled religious persecution;

A teetotaling temperance activist and Methodist minister who founded colleges out west, and his wife, who may or may not be a relative of Oliver Hazard Perry;

A Kentucky couple that used family ferry boats to bring people who had escaped from slavery across the Ohio River as part of the Underground Railroad.

My mom’s side does not quite have the same tall tales as my dad’s side does. Her tree, though, boasts veterans of both World Wars and immigrants from Italy, Germany, Sweden, and maybe Switzerland.

Genealogy was the hobby that my mom took up when I went to college, and I know that she has done much of her side already. She carefully scrapbooked out her lineage and gave copies to her siblings for their benefit. So I’ve spent my free moments in these past couple weeks digging through records on Family Search trying to confirm and extend what I already know about the people who make up my family tree, especially my dad’s side where the potential for excellent stories seems so great. Much of my experience with genealogical research is doing research into local history for the organizations I’ve helped in the past—genealogical resources can provide the most accurate information faster than any other source. There’s probably an essay to be written about the democratic nature of these primary sources and the guarantee that so many people have had their names inscribed in documents for their ancestors to find.

It’s exhilarating to use the expertise I’ve honed professionally to discover more about my heritage, especially when it intersects with touchstones I have from research for work. That prior knowledge helps me imagine the interior lives of my ancestors who spread across the true Midwest and the Great Plains in the middle of the nineteenth century. For example, I spent two years serving as an AmeriCorps Member in Oberlin, Ohio, where religion and temperance activism went hand in hand throughout the city’s history. This helps me see my ancestor, the minister and temperance activist, through their eyes because I understand why Oberlinians had signed on to the cause. Coupled with my dad’s memory of my grandmother saying she had never found him to be that kind or attentive (despite that he was her grandfather!), I have learned much more about the ingredients that compose my people today.

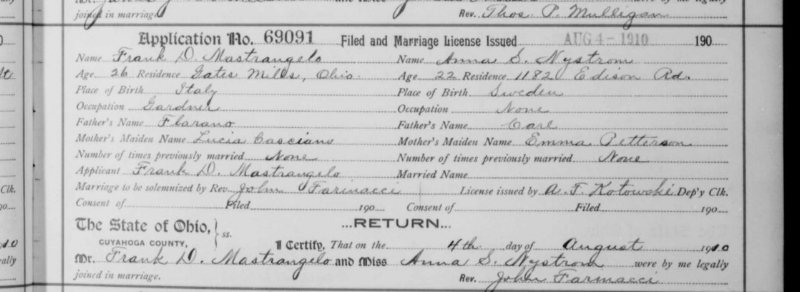

The marriage record for my great-grandparents.

Some caveats: it bothers me that you often cannot see the actual documents when you’re using a site like Family Search, and that means I cannot verify connections or spellings with the certainty that I would like as a historian. Sometimes results don’t come up in searches, even when I know I spelled names right, because they were transcribed incorrectly—“Amna” instead of “Anna” in a census record. Sometimes whole lines of family tree results come up incorrectly because another user has mapped a line based on their belief that they have the right information. For example, the father of the supposed Underground Railroad conductor’s wife currently has three contemporaneous wives listed. I am not currently sure which one is right, but the WASPy nature of the family tree makes certain that there can be only one.

I know I’m lucky to know so much about my family history already, and I am lucky to be able to apply my training and resources to finding out more. It’s weird to know that some of my ancestors are all over the historic texts on Google books. Of course, other ancestors, ones that I would like to know so much more about, have barely left a trace—they left only what my parents can tell me now.