One of the most fascinating exhibitions I saw during my recent travels was also the cheapest—it was free! In the Rotterdam Public Library, a building with yellow pipes down the side that make it look more like a factory, they have an exhibit called the Erasmus Experience, which focuses on the contributions of the humanist thinker Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536), who originally came from Rotterdam. It seemed like posters for the exhibit were placed throughout the city in places where interested people might be likely to find them—for me, it worked.

Exterior of the Rotterdam Public Library (my photo).

The exhibition focused on the philosophy of Erasmus and its resonance for the present-day, which is a lofty subject for an exhibit, especially in an age where people are resistant to reading large amounts of wall text. He wrote prolifically about the benefits of education and how, in the wake of the Reformation, every person could define their individual relationship with religion. Appropriately, Erasmus loved words and language, and the Erasmus Experience effective spun words into memorable edutainment for the afternoon.

And so I walked into the Rotterdam Public Library, peering across the rotunda for barriers to entry or signs directing me to the exhibition. I walked through a photography exhibit, through an area with a reference desk—a reminder that public libraries look much the same wherever you might be. I saw a sign directing me up to the next floor, and so I hopped on the escalator. At the top of the escalator, I saw a kiosk display on Erasmus that used the graphics for the exhibition; inside a small niche in the display rested postcards with Erasmus quotes on them. I enthusiastically snagged one as a free souvenir and continued on my merry way around the floor to the next escalator. Two more floors later, through the children’s section, and the romance section, I found myself staring at the alcove that held the Eramus Experience.

Screenshot of the Erasmus Experience website.

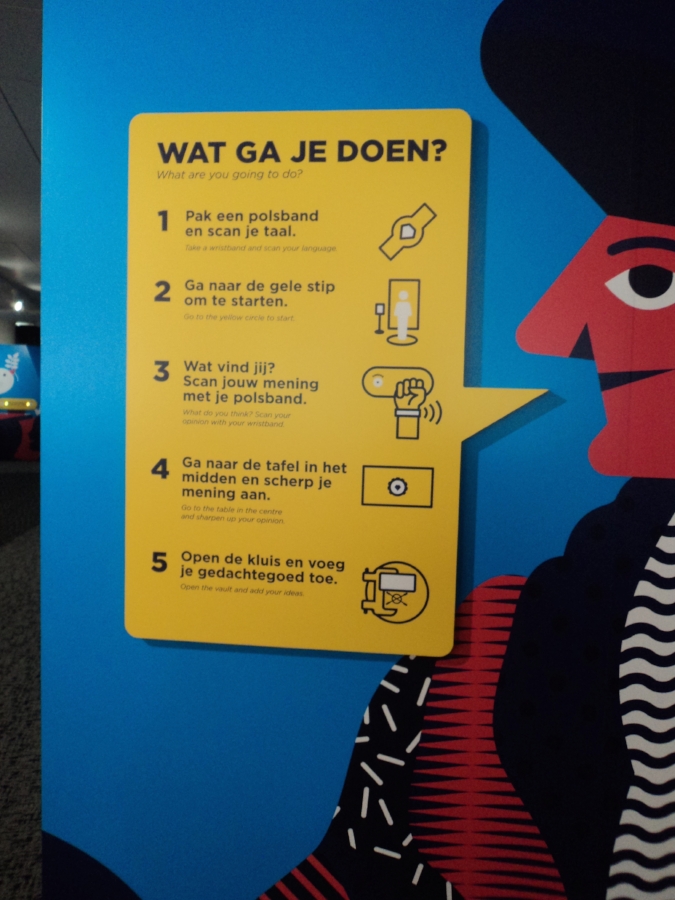

I had expected the space to be small, as library exhibitions often are, but they used the space well. Exhibition panels lined the wall of the alcove, with all the materials in Dutch and English, and a desk-style bank of flatscreen monitors filled the center of the room. The instructions clearly indicated that visitors should start with the wall panels and would end with the computer interactives. However, before entering, the instructions directed me to grab a little yellow bracelet—it looked almost like a FitBit or a large plastic kids’ watch—and stand on a mark to have my picture taken. The quick video and the sign (pictured below) explained that it would be my task to use the yellow bracelet to interact with the exhibit and collect “diamonds” for answering questions related to the opinions expressed by Erasmus. Gamification in museums—turning a learning task into a game with tasks and rewards—can be risky.

Sign at the beginning of the Erasmus Experience.

My instinct is always to be skeptical about exhibitions that require participation because they do not often manage to sustain that engagement all the way through the display. They ask too much or too little to really work effectively. In this case, however, I found myself reading the exhibition panels and swiping my little yellow bracelet to get those diamonds, almost without thinking about it and even though I had intended this exhibit to be a short stop in a jam-packed day of site-seeing. For example, a panel might describe what Erasmus had said about language, its rules, and its potential for connection, and the question it poses might be: “Do you believe that everyone should speak the same language in order to promote connection?” The answers might be something like “Yes, I do because how else can we understand each other?” and “No, I don’t because we should preserve the integrity of individual languages.” Answering the questions required thought and asked you to really understand why Erasmus held such beliefs. The exhibition also did an excellent job of placing Erasmus into a modern context—for example, because he lived in a time when most scholarship and religious activity occurred in Latin, he understood what it meant for a group of people, regardless of national boundaries, to all know one language. He understood the cloistered, classist nature of that shared Latin knowledge, but he was also willing to pose the question of what it might look if such a practice spread to the rest of society. I found the entire exhibit fascinating, and I wish I could share the whole thing with you here.

After making it through the all of the questions and collecting enough diamonds, you proceeded to the center of the room, where you could explore your answers further. A stylishly animated little Erasmus, like the one in the pictures above, interrogated your opinions in the style of a text message screen, occasionally playing devil’s advocate and pushing you to be sure you understood the consequences of your answers. You could do as much or as little of this interactive as you liked, and I found that it further deepened what I had already learned from the display. I also noticed, at this point in the exhibition, that there were cases filled with books, in the more traditional manner of library exhibition. But even though the Rotterdam Public Library claims one of the largest collections of Erasmus writings in the world, they did not rely on the objects themselves to engage visitors. Instead, they simply offered them as a bonus for those interested.

I left that day excited about Rotterdam's museums, and excited to learn more about Erasmus. It’s a shame that other texts on the philosopher—who seems extraordinarily relevant to today—are not as accessible as the Erasmus Experience exhibition was. In this case, “Experience” was not simply a flashy moniker to draw in numbers. The exhibition engaged me in his philosophy, provided a model for using technology to amplify learning, and incorporated traditional methods of display to emphasize the strengths of its collections. I saw a number of other museums and special exhibitions on my trip that tried to achieve these goals, but this is one of few that I’m still thinking about.